Miocene vertebrates from Entre Ríos province, eastern Argentina

Alberto Luis CIONE 1 , María de las Mercedes AZPELICUETA 2 , Mariano BOND 1 , Alfredo A. CARLINI 1 , Jorge R. CASCIOTTA 2 , Mario Alberto COZZUOL 3 , Marcelo de la FUENTE 1 , Zulma GASPARINI 1 , Francisco J. GOIN 1 , Jorge NORIEGA 4 , Gustavo J. SCILLATO-YANÉ 1 , Leopoldo SOIBELZON 1 , Eduardo Pedro TONNI 1 , Diego VERZI 2 , María Guiomar VUCETICH 1

Resumen.- VERTEBRADOS DEL MIOCENO DE LA PROVINCIA DE ENTRE RÍOS, ARGENTINA. La diversa fauna de antiguos vertebrados que se registra en los acantilados que bordean la margen oriental del río Paraná cerca de la ciudad de Paraná, provincia de Entre Ríos, Argentina se conoce científicamente desde la primera mitad del siglo XIX. En esos sedimentos se han colectado numerosos vertebrados de agua dulce, marinos y terrestres. Los fósiles proceden casi exclusivamente de la Formación Paraná (taxones marinos y de agua dulce: elasmobranquios, teleósteos, cetáceos, sirenios y pinnípedos) y en el "Conglomerado osífero" ("Mesopotamiense" auctorum) en la base de la Formación Ituzaingó (taxones marinos, de agua dulce y terrestres: elasmobranquios, teleósteos, cocodrilos, quelonios, aves y diferentes grupos de mamíferos. Los cetáceos sugieren que al menos el tope de la Formación Paraná es Tortoniano (Mioceno Tardío). El término "Piso Mesopotamiense" o "Mesopotamiense" es considerado inválido. El "Conglomerado osífero" parece representar un corto lapso. La fauna terrestre sugiere una edad Huayqueriense (Tortoniano) para el "Conglomerado osífero". La evidencia de vertebrados y las relaciones estratigráficas confirman la correlación de al menos la base de las capas puelchenses del subsuelo de la región pampeana con la Formación Ituzaingó. De acuerdo a la evidencia que aportan los cetáceos y los peces, las temperaturas marinas durante la depositación de la parte superior de la Formación Paraná eran similares a aquellas presentes en la plataforma atlántica actual a la misma latitud. Tanto la fauna terrestre como la de agua dulce del "Conglomerado osífero" indican un clima más cálido que el actual. Los vertebrados de agua dulce sugieren importantes conexiones entre las cuencas hidrográficas del sur y del norte de América del Sur. Los restos de aves y de mamíferos (y plantas) sugieren la presencia de áreas forestadas a lo largo de las costas de los ríos donde se depositó el "Conglomerado osífero" y áreas abiertas cercanas.

Introduction

The fossiliferous beds in the Paraná eastern riverside cliffs near the city of Paraná, eastern Argentina have been scientifically known since 1827 when Alcide D’Orbigny visited the area (D’Orbigny, 1842; Figures 1,2). The cliffs are extremely rich in marine and continental aquatic and terrestrial vertebrate remains. However, most of the collections were done without accurate stratigraphic provenance. For this, during many years it was debated if the material came from 1 Departamento Científico Paleontología Vertebrados, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, 1900 La Plata, Argentina. E-mail: acione@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar, azpeli@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar, palvert@museo.fcnym. unlp.edu.ar (Bond), acarlini@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar, jrcas@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar, mdelafu@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar, zgaspari@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar, fgoin@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar, palvert@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar (Scillato), palvert@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar (Soibelzon), eptonni@museo.fcnym. unlp.edu.ar, dverzi@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar, vucetich@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar. 2 Departamento Científico Zoología Vertebrados, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, 1900 La Plata, Argentina. E-mail: dverzi@museo.fcnym.unlp.edu.ar. 3 Universidad Federal de Rondônia, Porto Velho, RO, Brasil. E-mail: cozzuol@enter-net.com.br 4 Centro de Investigaciones Científicas y Transferencia de Diamante, Dr. Materi y España 3105 Diamante, Argentina. E-mail: cidnoriega@infoshopdte.com.ar. one level or another. Moreover, differerent marine levels were identified in the cliffs. Presently, several of us are making new collections with accurate stratigraphic provenance in the cliffs between Pueblo Brugo and Diamante (ALC, JN, MMA, JRC, EPT) with finantial support of the CONICET and ANPCYT. We are confident that many of the present uncertainties will be set with this field work. In this paper, the vertebrate record from the marine and continental Miocene units in the Paraná area is briefly revised by different specialists and a preliminary revised list is apported. Finally the correlation of the bearing units, and climatic and biogeographic aspects are discussed. We include great part of the literature dealing with Miocene vertebrates from Paraná área. The taxonomic lists include those taxa that are considered relatively well identified. Certainly, the investigations are in progress and, in the following years, many of the taxonomic assignations will be modified and new taxa will be included in the lists by means of new findings or the study of previous collections.

History

When Florentino Ameghino, in his important work on the extinct mammals of Argentina (1889), discussed the vertebrates from the «Piso Mesopotámico» of Doering (1882), he included about 90 mammal species in addition to fish and reptiles. This paper by Ameghino was a peak in the knowledge of the Miocene vertebrates from the Paraná area, which had begun with the visit of D´Orbigny to the area in 1827 (Figure 1).

The French researcher Alcide D´Orbigny arrived in America in 1826. In the next year, he explored the Paraná riverside cliffs near the city of the «Bajada de Santa Fé,» a former name for the city of Paraná, and later (1842) described the stratigraphy and many fossils. One of these fossils was a species of the endemic ungulate genus Toxodon described by Laurillard in D´Orbigny (1842); the species was different from the more recent Toxodon platensis, described by Owen and coming from the «arcilla pampeana.» D´Orbigny, based on the invertebrates, correctly attributed a Tertiary age to the sediments.

Another famous scientist, Charles Darwin, visit the area during October, 1833. Darwin described the stratigraphy of the cliffs near Paraná. In a bed near the base of the ravines, he found shark teeth and invertebrates pertaining to extinct species. Above this level, Darwin found a consolidated bed that passed upward to typical Pampean sediments. Darwin interpreted that as the result of a large marine encroachment which was gradually tranformed in a muddy estuary where corpses floated (Darwin, 1839).

The General Justo José de Urquiza, first president of the Confederación Argentina, with capital in the city of Paraná, propitiated the beginning of systematic geological and paleontological research in the riverside cliffs. Urquiza hired, among others, the belge Alfred Du Gratty, who in 1854 was director of the Museo de la Confederación in Paraná; the French physicist and naturalist Martin de Moussy, who was in charge of surveying the national territory; and the French architect (and amateur paleontologist), August Bravard, whose first assignment was surveying mineral deposits.

Bravard was appointed director of the Museo de la Confederación in 1857. A year later, the Registro Oficial de la Confederación published the «Monografía de los terrenos marinos terciarios de las cercanías de Paraná» (Bravard, 1858). This paper was the sum of his research which had previously been communicated in the natural history societies of Buenos Aires and Paris in 1855 and 1856, respectively. Bravard´s paper agreed in several respects with the observations

of D´Orbigny and Darwin but was in contradiction with the conclusions of a paper by De Moussy (1857).

Bravard (1858) described for the first time several teleosts and elasmobranchs, reptiles (including chelonians, ophidians and crocodiles), and mammals. The president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento sent the materials collected by Bravard to the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural of Buenos Aires. Mammals were represented by a whale and a rodent smaller than «Megamys patagoniensis,» described by D´Orbigny (1842) from the río Negro riverside cliffs near Carmen de Patagones (northern Patagonia). Bravard considered that the Paraná and Patagones beds were of similar age.

In 1861, Bravard died during an earthquake that destroyed the city of Mendoza (western Argentina). After Bravard (1858), the only publication in many years was the «Description Physique, Géographique et Statistique de la Confederation Argentine» (De Moussy, 1860).

The Museo de la Confederación was refounded as the Museo de la Provincia de Entre Ríos in 1884 and the teacher Pedro Scalabrini was its director since 1886. Scalabrini was a great fossil collector and soon was in contact with the great paleontologist Florentino Ameghino who eventually will describe the new material. This association was the origin of the knowledge of the mammal fauna from the «Piso Mesopotamiense» (Ameghino, 1883a, 1883b, 1885, 1886, 1889).

Between 1890 and 1892, the Swiss Kaspar Jacob Roth (Santiago Roth in the Argentinian literature; see Bond, 1999), surveyed the provinces of Entre Ríos and Corrientes. Roth made an important vertebrate collection from the «Conglomerado Osífero» of the Ituzaingó Formation, part of which was deposited in the Museo de La Plata, where he was appointed Head of the Sección Paleontología in 1895.

During the last part of the XIX and the beginning of the XX centuries, many amateurs collected near Paraná. Later, most of these private collections were deposited in the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural of Buenos Aires (Lelong Thévenet, Carles, Sors Cirera and Caixo collections) and Museo de La Plata (Sors Cirera). Other institutions where collections from Paraná area can be found are: Muséum National d´Histoire Naturelle of Paris and Natural History Museum of London.

During the XX century, since the important paper by Frenguelli (1920a), many authors published contributions on the paleontology and geology of the Paraná area (eg Bianchini and Bianchini, 1971; Aceñolaza, 1976; Aceñolaza and Sayago, 1980; Iriondo and Rodríguez, 1973; Noriega, 1995 and the bibliography cited therein).

Stratigraphic provenance of the Miocene vertebrates

The complex relationships between the marine and continental units cropping out in the cliffs provoked different interpretations. Most authors identified only one marine unit recognizable at the base of the cliffs (eg Ameghino, 1906; Scartascini, 1954; Aceñolaza, 1976).

This marine unit is overlain by a thick fluvial and a terrestrial sequence. However, other authors proposed two or three marine transgressions (Frenguelli, 1920a; Cordini, 1949). The current stratigraphic scheme was proposed by Aceñolaza (1976; see also Aceñolaza and Aceñolaza, 1999; Figure 2) who interpreted the marine rocks as having originated during a single ingression represented by the Paraná Formation. Aceñolaza (1976) suggested that the marine beds located at higher levels in the riverside cliffs are relicts of an ancient topography that was wrongly

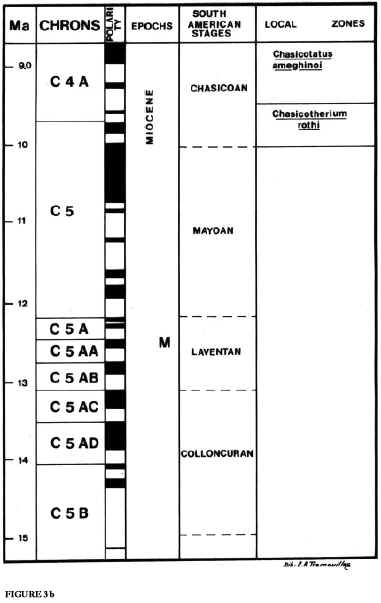

interpreted as different marine ingressions, especially by Frenguelli (1920a). The Paraná Formation is mainly composed by green mudstones and sandstones with oyster banks (Aceñolaza, 1976; Chebli et al., 1989). The Paraná Formation was apparently deposited during the large marine encroachment that covered the Chacopampean region during the middle Miocene ("Mid Transgressive Onlap Sequence;" see Uliana and Biddle, 1988; del Río, 1991). This trangression probably persisted in the East of Argentina until the Tortonian (see below). The fluvial Ituzaingó Formation overlies the marine unit. This formation is composed of a basal conglomerate ("Conglomerado osífero") with abundant vertebrate remains which is overlain by almost unfossiliferous whitish to yellow brown sandstones and green mudstones. Terrigenous Pleistocene (Ensenadan to Lujanian in the southern South American continental scale; see Cione and Tonni, 1995, 1996; Figure 3), poorly fossiliferous beds assigned to different units overlay the Ituzaingó Formation (Aceñolaza, 1976; Iriondo, 1980; Chebli et al., 1989). The Ituzaingó Formation (as Entre Ríos Formation) was correlated with the "Formación Puelche" of the Buenos Aires province subsoil (Reig, 1957; see below). According to the mammals occurring in the "Conglomerado osífero" and the stratigraphic relationships, the age of the base of Ituzaingó Formation is almost exclusively Tortonian (late Miocene) or Huayquerian in the local chronology (Pascual and Odreman Rivas, 1971; Cione, 1988; Figure 3; see discussion below).

The term "Piso Mesopotamiense" or "Mesopotamiense" was widely in use in the Argentinian vertebrate paleontology literature. This term was used for the first time by Doering (1882; see also Ameghino, 1883). Frenguelli (1920a) restricted the "Mesopotamiense" to the "Conglomerado osífero." Two of us discussed extensively the use of state/age concept in South America (Cione and Tonni, 1995, 1996) although we did not adressed the "Mesopotamiense" problem.

Cozzuol (1993) proposed to define the "Mesopotamiense" as a formal stage/age unit.

Unfortunately, most of the fossils in collections from the Paraná area do not include adequate provenance. Labels in collections usually only state that the material come from the base of the cliffs near Paraná. However, after several campaigns, we confirmed that almost all the Miocene terrestrial and freshwater aquatic vertebrates come from the «Conglomerado Osífero» at the base of the Ituzaingó Formation. Field work is presently in progress and more precise information will be obtained. The «Conglomerado osífero» occurs in paleochannels, is laterally interrupted and rarely crops out because landslides. We do not find adequate to sustain a chronostratigraphic, biostratigraphic, geochronologic or even biochronologic unit based on the fossil and stratigraphic representation of the «Conglomerado osífero.» Consequently, we consider here the «Piso Mesopotamiense» sensu Frenguelli (1920a) or «Mesopotamiense» as invalid. In this paper, we will refer to the fossil content of the base («Conglomerado osífero») of a lithostratigraphic unit (Ituzaingó Formation) as present in several localities near Paraná without recognizing a local chronostratigraphic or biostratigraphic unit (Figure 2).

Some marine vertebrates (mainly sharks and rays) occur in the «Conglomerado osífero.» It has to be determined if the marine vertebrate remains were reworked from the Paraná Formation or they actually inhabited the channels were the «Conglomerado osífero» was deposited. Until now, we have corroborated that the Paraná Formation includes mainly marine, some freshwater and no terrestrial vertebrate. In sum, present evidence indicates that most of the Miocene material from the Paraná area come from the marine Paraná Formation (elasmobranchs, teleosteans, cetaceans, sirenians and pinnipeds) and the «Conglomerado Osífero» at the base of the continental Ituzaingó Formation (elasmobranchs, teleosteans, crocodilians, chelonians, birds, and different groups of terrestrial and aquatic mammals).

The marine vertebrate record

Chondrichthyans

(Alberto Luis Cione)

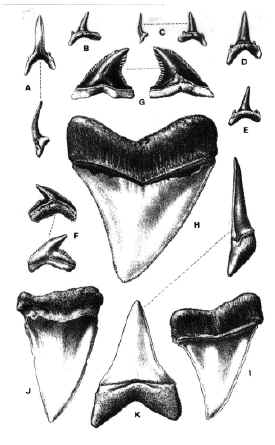

The marine elasmobranch fauna found in the Paraná Formation is composed by the odontaspidid Carcharias acutissima (abundant), the carcharhinids Carcharhinus spp.(abundant) and Galeocerdo aduncus, the heterodontid Heterodontus, the squatinid Squatina, the lamnid Isurus hastalis, the "otodontid" Carcharocles megalodon, the hemigaleid Hemipristis serra, the squalid Squalus, and batoids Dasyatidae and Myliobatoidei (D´Alessandri, 1896; Woodward, 1900; Priem, 1911; Frenguelli, 1920a, 1922; Cione, 1978, 1988; Arratia and Cione, 1996; Figure 4). The ichthyofauna has not been recently studied, but until now, there are no living species identified. Several of these species also occur (surely reworked in part) in the "Conglomerado osífero."

"Osteichthyans"

(Alberto Luis Cione, María de las Mercedes Azpelicueta and Jorge Casciotta) Some marine fishes were described from indeterminate beds near Paraná. The sparid Chrysophrys sp., Sparidae? indet., and the labrid Protautoga longidens Alessandri, 1896 were mentioned (Alessandri, 1896). The material was lost in the First World War in Torino, Italy.

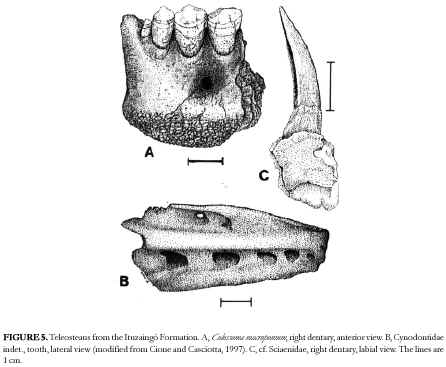

However, from the illustrations it can be observed that the presence of Sparidae and Labridae is not supported. The material identified as Sparidae? indet. (Alessandri, 1896) is quite similar to a lower pharyngeal plate of the sciaenid Pogonias cromis. We have found sciaenid remains both in the Paraná Formation and the "Conglomerado osífero" (Cione and Torno, 1984; Figure 5).

Cetaceans

(Mario Alberto Cozzuol)

The family Pontoporiidae, represented here by Pontistes rectifrons Bravard, 1858, and an indeterminate smaller species (Cozzuol, 1985, 1993, 1996) was a group diverse and widely distributed in the Americas both in the Atlantic and Pacific during the Cenozoic. Presently, only one species, Pontoporia blainvillei, which is an inhabitant of the Argentinian biogeographic Province in the Atlantic coast of South America, is extant (Ridgway and Harrison, 1989).

Physeterid and balaenid remains are not deteminable at lower taxonomic levels, but are similar to that of the recent species (Cozzuol, 1993, 1996).

Balaenoteridae are known by quite complete but undescribed cranial material, tentatively referred to the genus Balaenoptera (Cozzuol, 1993; 1996)

Sirenians

(Mario Alberto Cozzuol)

A tooth formely assigned to the genus Metaxyterium (see Reinhart, 1976; Cozzuol, 1993) is presently considered as pertaining, with doubts, to genus Dioplotherium (see Cozzuol, 1996). Remains of pachiostosic ribs are also relatively common in the collections. These bones are characteristic of the sirenians, specially of the paraphyletic family Dugongidae.

Aquatic carnivores

(Mario Alberto Cozzuol)

The phocid Properiptychus argentinus is one of the two fossil pinnipeds known from Argentina.

FIGURE 4. Neoselachians from the Paraná Formation. A-E, Carcharias acutissima; F, Galeocerdo aduncus; G, Hemipristis serra; H, Carcharocles megalodon; I-K, Isurus hastalis; Modified from Woodward (1900). All the material at natural size excepting H that is 2/3.

It was assigned to the paraphyletic subfamily «Monachinae» (see Muizon and Bond, 1982) and it was considered as primitive for the family, perhaps related to the paraphyletic genus Monachus (monk seals).

The continental vertebrate record

Chondrichthyans

(Alberto Luis Cione)

The genus Potamotrygon of the freshwater family Potamotrygonidae was mentioned by Ameghino (1898), without figuration or description. Recently, Deynat and Brito (1994) assigned the large dermal scutes described by Larrazet (1886) from Paraná to the family Potamotrygonidae.

Dernal scutes are found both in the marine Paraná Formation and the "Conglomerado osífero."

Part of the material probably correspond to other families.

«Osteichthyans»

(Alberto Luis Cione, María de las Mercedes Azpelicueta and Jorge Casciotta) Numerous specimens of catfishes and characiforms, taxa that include the most conspicuous Neotropical freshwater fishes were found in the Ituzaingó Formation (and also in the Paraná Formation; Figure 5). Fishes from the Paraná area have been known since last century (Bravard, 1858). However, they have not been adequately studied yet (Ameghino, 1898; Woodward, 1900; Priem, 1911; see Cione, 1978, 1986; Arratia and Cione, 1996). The catfish Silurus agassizi Bravard, 1858 was not described nor figured and must be considered nomen nudum (Cione, 1986). The assignation of a catfish skull to S. agassizi by Frenguelli (1920a) is obviously invalid. Catfishes of different families are present in the material from the "Conglomerado osífero" (ALC, personal observation). Some characiforms such as the serrasalmid Colossoma macropomus occur in the Ituzaingó Formation (Cione, 1986; Figure 5). This species has been also identified in La Venta Group (Middle Miocene of Colombia; Lundberg et al., 1986, 1988). The records from the Ituzaingó Formation and La Venta Group corroborate the

biogeographic relationship based on by other faunal elements (eg, crocodilians, trichechids, cetaceans).

Canine teeth of the characiform family Cynodontidae, similar to genera Hydrolicus, Cynodon and Raphiodon, were described from the "Conglomerado Osífero" (Cione and Casciotta, 1997; Figure 5). However, the size and position of serrae on cuttig edges is different from that recorded in species of these extant genera. One large tooth probably corresponds to a specimen of more than 1000 mm SL.

A tooth identified as pertaining to the ginglymodi Lepisosteus (Alessandri, 1896) is assignable to an indeterminate Crocodylia (Cione, 1986).

"Reptilians"

(Zulma Gasparini and Marcelo de la Fuente)

The first references of fossil crocodiles, turtles and ophidians of Argentina, are those of Bravard (1858). Further papers, describing fragmentary material from the "Conglomerado osífero," supported the determination of numerous species of chelids, testudinids, alligatorids, gavialids, and teiids (Burmeister, 1885; Ambrosetti, 1890, 1893; Wieland, 1923; Rusconi, 1933, 1934, 1935; Mones, 1986). However, this high diversity was reduced by more recent studies (Báez and Gasparini, 1977; Donadío, 1983; Gasparini et al., 1986, de la Fuente, 1988, 1992; Broin and de la Fuente, 1993; Albino, 1996; Gasparini, 1996; Langston and Gasparini, 1997).

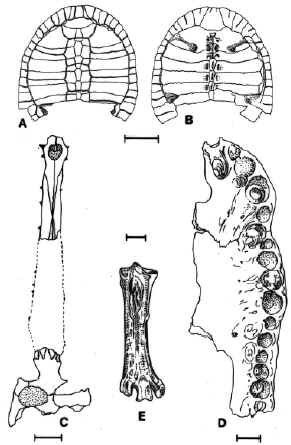

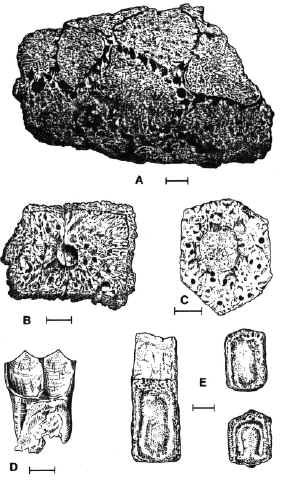

A single chelid (Phrynops cf. Phrynops geoffroanus complex) (see Rhodin and Mittermeier, 1983; Figure 6), one indeterminate testudinid, three species of alligatorids (Caiman jacare, C. latirostris and probably C. australis; Figure 6), one nettosuchid (Mourasuchus nativus), one gavialid (Gryposuchus neogaeus; Figure 6), and one teiid (Tupinambis cf. T. merianae) are presently accepted.

The diversity of crocodiles in the area of Paraná may be compared to that recorded currently in the basins of the large northern South American rivers, such as Paraguaí and Solimões rivers in Brazil and Madre de Dios river in Perú (Medem, 1983). However, it is richer at the familial level, as there are gavialids (currently limited to southeastern Asia) and netosuchids (extinct).

Likewise, Caiman jacare and Caiman latirostris were recorded in "Conglomerado osífero;" both species inhabiting nowadays the Mesopotamian margin of the Paraná river basin.

Chelonian diversity is lower at the familial and generic level than that of other coeval South American sites. For example, podocnemidids are not represented in the Ituzaingó Formation; among chelids, no species referable to Chelus has been recorded, and the diversity of testudinines is much lower (cf Lapparent de Broin et al.,1993, and literature therein; Wood, 1976, 1997; Wood and Díaz de Gamero, 1971). Concerning chelid turtles, the greatest generic and even specific affinities is found to chelids of the Kiyú Formation, Department of San José, Uruguay (cf Perea et al., 1996; their Figure 2).

Birds

(Jorge Noriega)

The bird record from the «Conglomerado osífero» comprises eight species of six orders: Pelecaniformes, Charadriiformes, Anseriformes, Ciconiiformes, Rheiformes and Gruiformes.

The Pelecaniformes are represented by the largest known darter (Macranhinga paranensis, Anhingidae; Figure 6). This species showed mechanisms of aquatic and aerial locomotion simiar to those of the recent putative sister group of the Anhingidae, i.e. the family Phalacrocoracidae (Noriega, in press).

Another indeterminate darter seems to have been a flightless species, with a size similar to

FIGURE 6. "Reptiles" and bird from the Ituzaingó Formation. Phrynops cf P. geoffroanus, caparace: A, dorsal view; B, visceral view (modified from Wieland, 1923); the line is 10 cm. C, Gryphosuchus neogaeus, skull, dorsal view (modified from Gasparini, 1968); the line is 10 cm. D, Caiman latirostris, skull, ventral view view (modified from Gasparini, 1968); the line is 2 cm. E, Macranhinga paranensis, tarsometatarsus, anterior view (modified from Noriega, 1992); the line is 1 cm.

the recent species Anhinga anhinga (Noriega, 1994, 1995).

The Charadriiformes record include an indeterminate species of genus Megapaloelodus from the extinct flamingo family Palaeolidae and an indeterminate Phoenicopteridae (Noriega, 1995).

The only fossil South American representant of the subfamily Dentrocheninae (Anseriformes, Anatidae) occurs in the «Conglomerado osífero.» This subfamily is more related to the Dendrocygninae (whistling ducks) and Anserinae (geese and swans) than to the real ducks (Anatinae; Noriega, 1995).

The ciconiiform Mycteriini storks are only known in the Tertiary of South America in the «Conglomerado osífero» (Noriega, 1994, 1995).

Cursorial birds are represented by indeterminate reiform Rheidae, gruiform Rallidae and Phororhacidae (Noriega, 1995). This last family includes the large phrorhacine Onactornis? and the medium sized palaeociconine Andalgalornis. Phororhacid taxa from the «Conglomerado osífero» must be revised (Noriega, 2000).

Marsupials

(Francisco Goin)

Three carnivorous marsupials (Sparassodonta), and three "opossum-like" marsupials (Didelphimorphia) are known from the "Conglomerado osífero:" Notictis ortizi Ameghino 1889 (Sparassodonta, Hathliacynidae) is a very small hathliacynid solely represented by a partially preserved dentary. Stylocynus paranensis Mercerat 1917 (Sparassodonta, Borhyaenidae, Prothylacyninae) is one of the largest known prothylacynine marsupials. Its mandibular and dental specializations suggest a predominantly omnivorous diet (Marshall, 1979). Achlysictis lelongi Ameghino 1891 (Sparassodonta, Thylacosmilidae), one of the most spectacular, large predaceous marsupials evolved in South America, is also present at Paraná deposits. Goin and Pascual (1987) proposed to keep the name Thylacosmilus atrox to this and all other late Miocene-Pliocene known thylacosmilids (but see Marshall et al., 1990). Philander entrer rianus Ameghino 1899 (Didelphimorphia, Didelphidae, Didelphinae) is probably a synonym of the Recent Philander opossum, and its stratigraphic provenance ("Conglomerado osífero") should be regarded as highly dubious (Goin, 1997b; see below). Chironectes sp. (Didelphimorphia, Didelphidae, Didelphinae), also recorded from "Barrancas del Paraná, Mesopotamiense" (original label) is also a probable synonym of the Recent species Chironectes minimus (Reig, 1958; Reig et al., 1987; Marshall, 1987; but see Goin, 1991). It is another case of a possible Recent opossum mixed among "Mesopotamian" taxa. Zygolestes paranensis Ameghino 1898 (Didelphimorphia, Didelphidae, Marmosinae) is a curious, tiny marmosine opossum whose affinities were unclear until veryrecent times. On account of its peculiar features noted by Reig (1957) in his diagnosis of the species, Reig et al. (1985, 1987) regarded it as a Didelphoidea incertae sedis. Marshall (1987) and Marshall et al. (1990) recognized for it a new Tribe among the Didelphinae: Zygolestini. Goin (1991, 1995, 1997b) and Goin et al. (MS) argued in favour of its Marmosini affinities, especially with species of Gracilinanus. A recently described new species of Zygolestes, from Huayquerian levels of Pampean area, suggests to Goin et al. (in preparation) that a Miocene age for Zygolestes paranensis is reasonable.

Xenarthrans (Figure 7)

(Gustavo J. Scillato Yané and Alfredo A. Carlini)

Except for a few prior findings of vertebrates that have only historical interest, the discovery

FIGURE 7. Xenarthans and litoptern from the Ituzaingó Formation. A, Palaeohoplophorus scalabrinii., lateral view of causal tube. B, Pseudoeuryurus lelongianus, dermal scute of the dorsal caparace. C, Scalabrinitherium bravardi, upper molar. D, Palaeohoplophorus scalabrini, dermal scute of the dorsal caparace. E, Kraglievichia paranensis, dermal scutes in dorsal view. (A-D, modified from Ameghino, 1889; E, modified from Edmund, 1987). The line is 1 cm. and study of the xenarthrans from the Ituzaingó Formation began with the collections of Pedro Scalabrini. He sent the remains to F. Ameghino for study (see Ameghino 1883, 1883a, 1885, 1886 and 1889). Later, numerous xenarthrans, mainly tardigrades, were re-studied or recognized as new ones by L. Kraglievich (1922, 1923, passim) and Scillato-Yané (1975a, 1980, 1981, 1982; Pascual et al. 1990). Recently, in relation with new collections, different remains of tardigrades were described from the Ituzaingó Formation and systematic and biostratigraphic problems were addressed (Carlini et al. in press). Likewise, a complete list of the xenarthran species of the Argentine Cenozoic distributed according to stratigraphic units and geographic areas is given elsewhere (Scillato Yané and Carlini, in press). In these analyses, the xenarthran diversity from the Ituzaingó Formation (42 genera and 56 species, see Table 1) is found to be exceeded only by that of the Santa Cruz Formation (Santacrucian, early Miocene from Patagonia), and much greater than that of any other South American unit. However, the nature of the deposits and the fragmentary and dissociated remains have led to both an overestimation of the diversity (by recognizing species based on non-homologous remains), and an underestimation when the assignment of specific differences was impossible in view of the fragmentary materials.

Among the Cingulata, dasypodids are very scarce in the "Conglomerado osífero," all the cited species being known by a single specimen, except for Proeuphractus limpidus. This is particularly outstanding, especially in comparison with the abundant record in the coeval sites of northwestern Argentina.

The record of Zaedyus is dubious in view of the poor material. Besides, the occurrence of this taxon disagrees with the remaining taxa, because it is typical from relatively cold and xeric regions.

Pampatheres were hitherto represented by a single but quite frequent species, Kraglievichia paranense. Recently, a new species of genus Scirrotherium was identified in the "Conglomerado osífero" and will be described in a future paper. The genus Scirrotherium occurs for the first time outside the middle Miocene of La Venta (Colombia).

Glyptodontids are very diversified in the Ituzaingó Formation (12 genera and 12 species).

The tribe Palaehoplophorini is highly dominant in taxic composition which is in contrast with the "Araucanian" of northwestern Argentina, where they are absent, and the very scarce record in the Miocene-Pliocene of the Pampean region. The occurrence of Berthawyleria (Miocene-Pliocene from Uruguay and Pliocene of the Pampean region) is the first for the Ituzaingó Formation. "Hoplophorus" verus des not belong in this Pleistocenic genus, but perhaps in Hoplophractus Cabrera or Eosclerocalyptus C. Ameghino. The available material of Trachycalyptus? cingulatus is not enough to determine whether it is assignable to this genus or to Comaphoropus.

The largest glyptodont of the Ituzaingó Formation is the neuryurini Urotherium interundatum, with a size similar to Neuryurus rudis (Pleistocene of the Pampean region). The doedicurine Comaphorus concisus is similar to Urotherium interundatum in the scute surface and the profile of the elevated central figure. Unfortunately, the material is not enough as to accurately establish the variability of the different carapace regions. However, caparace similarities clearly suggest a close relationship between Sclerocalyptinae Neuryurini and Doedicurinae (see also Ameghino 889:840 ss.). Pseudoeuryurus lelongianus also has a similar scute morphology to C. concisus and U. interundatum.

The diversity of the tardigrades from the Ituzaingó Formation is higher than that of any other unit of the late Miocene-Pliocene of Argentina. The 23 genera and 37 species recognized are distributed among the families Megatheriidae (Megatheriinae and Nothrotheriinae), Megalonychidae (Orthotheriinae, Megalocninae and Megalonychinae) and Mylodontidae (Mylodontinae, Octomylodontinae and Scelidotheriinae). These families include few small species

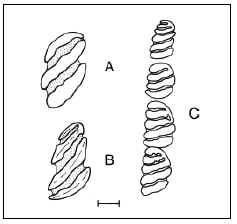

FIGURE 8. Rodents from the Ituzaingó Formation. A, Phoberomys sp., lower right molar, oclusal view. B, Phoberomys, lower right premolar, oclusal view. C, Eumegamys paranensis, lower right molariform series. Modified from Kraglievich, 1932. The line is 1 cm. but those middle and large sized are better represented.

Megatheriinae genera already cited in the Ituzaingó Formation are: 1- Eomegatherium (also in the Mayoan and in the upper Miocene of San Gregorio cliffs, Uruguay); 2- Promegatherium G(probably also in the basal beds of the Huayquerías Formation, late Miocene of Mendoza; and 3- Pliomegatherium, the only exclusive to the "Conglomerado osífero." These genera are represented by a smaller species with more primitive characters than those coeval from northwestern Argentina, the Huayquerías of Mendoza and northern Patagonia.

A right humerus, the measures of which reach those of Megatherium americanum is quite larger than the remaining megatherines and different in morphology to the other genera from the Ituzaingó Formation. However, when compared with remains of Pyramiodontherium from Catamarca ("Araucanian"), it seems to coincide in the diaphysis section and the progression of its proximal diameter. Consequently, we consider this fossil as pertaining to that genus (perhaps a new species; Carlini et al., in preparation). Pyramiodontherium, with a single species (P. bergi) has been hitherto recognized exclusively in the "Araucanian" of Catamarca and Tucumán.

The nothrotherine are represented by Neohapalops, an endemite, and Pronothrotherium, which is also known in the Miocene-Pliocene of the Uruguay and northwestern Argentina and the Pliocene of Mendoza and the Pampean region.

The diversity of Megalonychidae from the Ituzaingó Formation is higher than that of any other South American unit and only can be compared with that of the Pleistocene of West Indies. The "Orthrotheriinae" (which probably is not a natural group, Carlini and Scillato-Yané, Paranabradys and Orthotherium. The five nominated species of Orthotherium must be revised. Among megalonychids there are genera related to North American forms (Protomegalonyx, Megalonychinae) and to West Indies megalocnines (Amphiocnus, see Pascual et al. 1990 and probably Pliomorphus, in study). Megalonychops is the largest known Megalonychidae in the Ituzaingó Formation, comparable in size to Megatherium. Remains of Megalonychops, which also occurs in the Miocene-Pliocene of Uruguay and the Pleistocene of the Pampean region, are scarce in the "Conglomerado osífero" and need to be restudied. Diodomus copei is probably a Megalonychidae but the scarce remains should be revised.

Remains of mylodontid subfamilies are quite irregular in diversity and frequency.

Mylodontinae reach higher generic and specific diversity and abundance in the "Conglomerado osífero" than in any other Tertiary stratigraphic unit. They are abundant in the Miocene-Pliocene of northwestern Argentina but very scarce in coeval localities of the Pampean region.

The peculiar Octomylodontinae (see Scillato-Yané, 1977a) are only known in the "Conglomerado osífero" and the Vivero Member of the Arroyo Chasicó Formation in the Pampean region (represented by Octomylodon robertoscagliai).

The Scelidotheriinae are very scarce. We have seen molariforms of a rather large scelidotherine coming from the Ituzaingó Formation.

"Native ungulates" (Figure 7)

(Mariano Bond)

After the first descriptions by D´Orbigny (1842) and Bravard (1858), the systematic description of ungulates from Paraná begun in the decade of 1880 (Burmeister, 1885-1891 and especially Ameghino, 1883a,b, 1885, 1886, 1887, 1889, 1891, 1904a, b, 1906; Frenguelli, 1920b; Kraglievich, 1931, 1934). Pascual and Odreman (1971) apported a list and some comments. The study of protherotheriids by Bianchini and Bianchini (1971) is the only recent revision of native ungulates from the Ituzaingó Formation.

In the «Conglomerado osífero», the two orders that survived Chasicoan times are present: Litopterna (Macraucheniidae and Proterotheriidae) and Notoungulata.

Macraucheniids are represented by the sufamily Macraucheniinae, which is recorded since the Chasicoan (late Miocene). All macraucheniids recorded seem to be more generalized than Promacrauchenia (Montehermosan and Chapadmalalan) and more related to taxa from the Chasicoan and Huyquerian (Bond and López, 1996). The Proterotheriidae Proterotheriinae correspond to more generalized taxa than those from the Montehermosan while there persist some «Pansantacrucian» species. Comparing with other faunas from the late Miocene and Pliocene beds of Argentina, Bolivia and Uruguay, Litopterna are extremely abundant (as numerous as Notoungulata) in the «Conglomerado osífero.»

Notoungulata present diferences in diversity and systematic composition in relation to other faunas of late Miocene and Pliocene units of Argentina, Bolivia and Uruguay. There are no «rodentiform» Tipotheriidae, Hegetotheriidae Hegetotheriinae and Pachyrukhinae, nor Mesotheriidae Mesotheriinae while Hegetotheriidae, especially Pachyrukhinae, and Mesotheriidae are extremely frequent in the other localities.

The record of Mesotheriidae (Ameghino, 1906) and Pachyrukhinae (Pascual and Odreman Rivas, 1971) from the «Conglomerado osífero» seems to have been based on an erroneous identification (Kraglievich, 1931; Bond and López, 1998). However, in the «Conglomerado osífero» the last probable representants of the Interatheriidae Interatheriinae occur. Protypotherium antiquum is also the largest species of Interatheriinae, subfamily which is very frequent in the

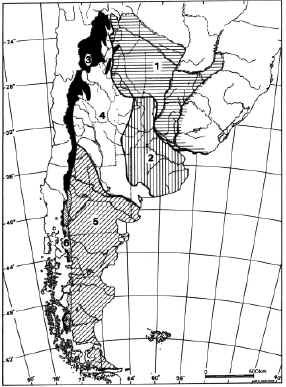

FIGURE 9. Zoogeographic pattern of Argentina (modified from Ringuelet, 1961). 1, Subtropical Dominion. 2, Pampean Dominion. 3, Andean Dominion. 4, Central or Subandean Dominion. 5, Austro-Cordilleran Dominion.

Santacrucian and Colloncuran of Patagonia. The interatheriins occurs in Chasicoan beds for the last time in the Pampas. Some probable Interatheriinae remains are assignable to the genus Munizia, an endemic and larger genus.

Toxodontids are the more abundant and diverse Notoungulata in the «Conglomerado osífero.»

Different groups with euhipsodont molariforms recognized from the Colloncuran, Mayoan and Chasicoan are present. The Xotodontinae and Toxodontinae include medium and large sized taxa and the Haplodontheriinae and Dinotoxodontinae with large to gigantic sized taxa. The supposed occurrence of Nesodontinae (Ameghino, 1891, 1906) is probably based on remains of a more advanced oxondontid known from the Huayquerian of Uruguay (?Berroia, Kraglievich, 1934). Xotodontinae have the last certain record in the Montehermosan and probably in the Chapadmalalan. Haplodontheriinae, large to gigantic toxodontids, include several taxa with a remarkable frontal bony protuberance which would indicate the occurrence of a «horn.» This family of «rinocerontid» notoungulates is recorded for the last time in the Montehermosan.

Dinotoxodontinae, a group not clearly defined of large toxodontids characterized by a notable lower projection of the mandibular symphysis, seems to have been abundant in the Pampean area during the Chasicoan and Huayquerian, and presents several forms in the «Conglomerado osífero.» The abundance of toxodontids appears to agree with the traditional atribution of semiaquatic habits, or at least relation with wet environments, of these notoungulates.

The toxodonts from the «Conglomerado osífero» have been described mainly on the basis of isolated teeth. However, they have been used for recognizing some subgroups inside the Family Toxodontidae (eg Haplodontherium and the Haplodontheriinae). Besides, it is evident that there is similitude between many taxa from the Ituzaingó Formation and those of the Miocene-Pliocene from Argentina, Bolivia and especially Uruguay and Acre in Brazil. For this, only a thorough revision of the taxa described for the Ituzaingó Formation will shed light not only on the systematic but on the relationships of these taxa with those from the other coeval units.

Rodents (Figure 8)

(María Guiomar Vucetich and Diego Verzi)

Hystricognathi rodents are represented by families Echimyidae, Myocastoridae, Caviidae, Hydrochoeridae, Dinomyidae, Neoepiblemidae, Chichillidae, Abrocomidae and Erethizontidae.

Probably there is no other so diverse (at familial level) rodent fauna in the Cenozoic of South America. Octodontidae is the only southern South American family that is not present. This familial diversity would indicate the influence of different biogeographic domains. For example, the presence of abrocomids and chinchillids suggests a connection with central and western Argentina while that of neoepiblemids indicate a clear connection with the Miocene beds of the Brazilian Acre region.

The rodent fauna of the "Conglomerado osífero" is also very rich at the generic level, including more than 40 genera. The richest families are Dinomyidae (16), Hydrochoeridae (9), and Caviidae (6). The remaining families are represented by one to three genera (Table 3 ). Rodents from the "Conglomerado osífero" have not been revised exhaustively after the original descriptions.

However, a preliminar revision of type and calcotypes indicates that some species are based on jaw fragments, or juveniles, and even on one isolated molariform. For this, it is probable that the number of species and genera could be overestimated.

Families Dinomyidae, Hydrochoeridae and Caviidae show their highest diversity in the "Conglomerado osífero," with several genera, some of which are endemites.

Recently, with the revision of the calcotype of Paradoxomys cancrivorus, a former enigmatic taxon, it was demostrated that it represents the first Erethizontidae for the "Conglomerado osífero." Paradoxomys cacrivorus seems to be related to the radiation of recent taxa more than to the Patagonian radiation (Vucetich and Candela, in preparation).

The presence of Protabrocoma, related to the genus Abrocoma is remarkable because this latter is restricted to the arid Andean region. The most plausible hypothesis is that Protabrocoma paranensis had environmental constraints different to the living species of Abrocoma. In this sense, it is remarkable the record of a recent unusual abrocomid, showing climbing capabilities, from the forested areas in the northern Vilcabamba cordillera (Bolivia; Cuscomys; Emmons, 1999).

Echimyids are represented by endemic taxa of the Eumysopinae. These taxa would represent different lineages to the Eumysopinae of the Late Miocene of central and western Argentina (Verzi et al., 1995; Vucetich and Verzi, 1995) and the Pliocene and Pleistocene of the Pampean area (Vucetich and Verzi, 1996; Vucetich et al., 1997).

A characteristic of the "Conglomerado osífero" (and coeval localities) is the presence of the largest representants of the order Rodentia (Neoepiblemidae, Hydrochoeridae and Dinomyidae).

Terrestrial carnivores

(Leopoldo Soibelzon)

The first procyonid carnivore recognized in Argentina is the procyonine Cyonasua argentina (see Ameghino 1885, 1886) from the "Conglomerado osífero." Procyonid are medium-sized, good swimmers omnivores that mainly inhabit forested environments (Bond, 1986). Their habits probably facilitated the early entrance of these carnivores as "waif immigrants" from North America during the Huayquerian (late Miocene; (Pascual et al., 1985).

Cetaceans

(Mario Alberto Cozzuol)

At least three species of the Family Iniidae and a Pontoporidae were described from the «Conglomerado osífero.» Ischyorhynchus vanbenedeni Ameghino, 1891 is the best known cetacean from the Paraná area (Cozzuol, 1993, 1996). It presents morphological adaptations for a turbid fluvial environment (Pilleri and Gihr, 1979).

Saurocetes argentinus Burmeister, 1871, also a relatively abundant species, is known by partial skulls and mandibles (Cozzuol, 1985).

Both species were also recorded in the Miocene beds of Acre and Uruguay (Boquentin et al., 1989; Rancy et al., 1989; Perea and Verde, 1982; personal observation, MAC).

Other species of Saurocetes, S. gigas (Cozzuol, 1989) is remarkable for its unusual size for a freshwater cetacean (about 4.5-5 m).

Sirenians

(Mario Alberto Cozzuol)

The occurrence of a Trichechidae (Ribodon limbatus Ameghino, 1883) at this latitude is important from a biogeographic and climatic perspective. But R. limbatus is also remarkable because this species shows a type of tooth change which is considered advanced in comparison with primitive trichechids, such as Potamosiren (from Laventan beds of Colombia) and considered a synapomorphy shared with the recent Trichechus (Domning, 1982; Cozzuol, 1993, 1996).

R. limbatus was also recorded in the Acre region, at the Peruvian-Brazilian border (Frailey, 1986; Cozzuol, 1993; 1996). A maxilar of a sirenian from the coastal plain of South Carolina, USA, was referred as belonging to an unidentified species of Ribodon (Domning, 1982). The age

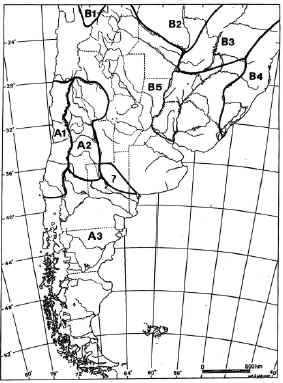

FIGURE 10. Ichthyogeographic «provinces» of southern South America according to Ringuelet (1975), modified by Arratia et. al (1983). A1-A3: Austral Subregion. A1, Chilean Province; A2, Cuyan Province; A3, Patagonic Province. B1-B18: BRazilian Subregion; B1, Titicaca Province; A3 Patagonic Province. B1-B18: Brazilian Subregion; B1 Titicaca Province; B2-B4, Paranean Domain; B2, High Paraguay Province; B3, High Paraná Province; B4, Pano-Platan Province; B5, coastal river of South eastern Brazil Province..

of the fossil was mentioned as probably early Pliocene. Taking into account those data, it seems that Ribodon had a similar geographic range than the living Trichechus, except by the African coast.

Stratigraphic correlation

Marine

Sharks are suggestive of Middle Miocene to Pliocene age but cetaceans suggest, more accurately, a Late Miocene age for the top of the Paraná Formation. The occurrence of Balaenidae and Physeteridae similar to modern taxa, of Balaenopteridae (unknown in beds older than late Miocene), and the lack of common taxa with the early Miocene Gaiman Formation (Cione and Cozzuol, in preparati n) and the Middle Miocene Puerto Madryn Formation (Cozzuol, 1993, 1996), suggests that he uppermost part of the Paraná Formation (at least in the outcrops in the bottom of the Arroyo Ensenada valley and Villa Urquiza) would be Tortonian in age. Besides, there are no outcrops with typically Chasicoan fauna (early Tortonian in age) overlying the Paraná Formation and underlying the «Conglomerado osífero» of the Ituzaingó Formation, where Huayquerian fauna occurs (see below). Certainly, both formations are separated by an important unconformity and an important lapse is perhaps not represented by sediments (and fossils).

Continental

The exact age of the Ituzaingó Formation has been largely discussed. Mammals from the Ituzaingó Formation are extremely diverse. At first sight, the coexistence of so many taxa would be suggestive of an artificial mixture, especially considering that the ecological requirements of many of them must have been very similar and the methodology of collection of former researchers. Some authors even proposed that the mammal material from the "Conglomerado osífero" could be redeposited from beds of different age: Chasicoan, Huayquerian, Montehermosan and even Santacrucian (Bianchini and Bianchini, 1971; Scillato-Yané 1977a, 1980, 1981; Marshall et al., 1983). Another important drawback is the accurate identification of taxa because most of the determinations are old and should be revised. Consequently, we believe that considerably field work and taxonomic studies should still be done in all Late Miocene units in southern South America.

However, we consider that:

1. The age of the "Conglomerado osífero" is constrained by that of the underlying Paraná Formation (Figure 2).

2. According to cetacean evidence, the top of the Paraná Formation seems to be early Tortonian in age.

3. There is an important unconformity between the Paraná and Ituzaingó Formations that could represent a relatively long lapse.

4. All the terrestrial vertebrate remains are disarticulated. However, this is usual in a fluvial deposit. The only articulated vertebrate recorded are some freshwater fishes very well preserved into nodules. Remarkably, many bones are unworn, especially taking into account the conglomeradic and sandy composition of the deposit. We regard unlikely that the material would come from other terrestrial units (which actually are unknown in the area; see also Cozzuol, 1993). Moreover, the fluvial basin developed onto the marine beds and there is no doubt that some (not necessarily all) marine vertebrates remains present in the "Conglomerado osífero" were reworked from the Paraná Formation. We did not find terrestrial vertebrates in the Paraná Formation so far.

5. The major affinities of the "Conglomerado osífero" are with Chasicoan and Huayquerian faunas (Figure 3; Tables 1-3). Genera shared (figure in parenthesis: certain records plus doubtful records): Chasicoan, 11 (17?); Huayquerian, 28(32?). We discard the correlation with Santacrucian, Mayoan, Laventan and Montehermosan. The occurrence of a few taxa with Santacrucian, Mayoan and Laventan affinities is here considered as the persistence of ancient lineages (see above). There are several other cases in the Cenozoic of South America.

Affinities with Montehermosan beds are reduced to the first occurrence in both unit of the species Macroeuphractus retusus (three scutes, see Scillato Yané, 1975b) and Protohydrochoerus (a molar, MGV, personal observation). Consequently, the discussion is reduced to the correlation with Chasicoan or Huayquerian beds.

6. The Chasicoan age was recognized on the basis of the stratigraphic and faunistic record of the Arroyo Chasicó Formation in southern Pampean region (for a comment see Bondesio et al., 1980; Marshall et al., 1983; Tonni et al., 1998). The Loro Huasi Formation (Valle de Santa María, Catamarca, Galván and Ruiz Huidobro, 1965; «Chiquimil» or «Chiquimil Formation» of other authors, see Marshall and Patterson, 1981) is perhaps correlated to the type Chasicoan (Marshall et al., 1983).

7. The Huayquerian age is mainly recognized on the basis of the stratigraphic and faunistic record of the Andalhuala Formation (Valle de Santa María, Catamarca, Galván and Ruiz Huidobro, 1965; «Araucanense» of Frenguelli, 1930; Riggs and Patterson, 1939 non «Araucanense» of Ameghino, 1906 and other authors, a much more embrancing concept) and the Epecuén «Formation» and Cerro Azul Formation (Pampean area; Pascual et al., 1965; for other Huayquerian localities, see Marshall et al., 1983). The Andalhuala Formation is represented by the levels XV to XX of Chiquimil area and 14 to 18 of Corral Quemado area, both in Catamarca province (see Stahelcker´s stratigraphic sections in Riggs and Patterson, 1939 and Marshall and Patterson, 1981). We proposed elsewhere that the levels 18 to 21 of Corral Quemado might not be Montehermosan but Chapadmalalan in age as well as several sections in Bolivia (Cione and Tonni, 1996).

8. For analyzing the first mammal occurrences in the Ituzaingó Formation and other sequences we preferred to use the fossil record of the Chasicoan type section, the Huayquerian Andalhuala Formation and the Huayquerian beds of the Pampean region. The Andalhuala Formation section should be the actual stratotype of the Huayquerian. The Arroyo Chasicó Formation is well sampled and is overlain by Huayquerian beds (Tonni et al., 1998). The thick sequences in the Catamarca province were well sampled, were radiometrically and magnetostratigraphically analyzed, and include a possible Chasicoan section (Loro Huasi Formation), a Huayquerian section (Andalhuala Formation), and a probable Chapadmalalan section. The Epecuén and Cerro Azul Formations do not crop out in a stratigraphic sequence with older and younger units but are rich in mammal content.

9. For correlation we considered relevant the first occurrences and the shared occurrence of several mammal taxa mostly at supraspecific level due to the lack of a recent systematic revision in most the groups.

10. The «Conglomerado osífero» shares first mammal occurrences with (Tables 1-3): 1) the Andalhuala Formation: Myocastoridae, Parahoplophorus, Pyramiodontherium, Pronothrotherium, Sphenotherus, Neuryurini (Urotherium) and Xotodon. 2) Huayquerian localities in Buenos Aires and La Pampa provinces: Caviodon, Protabrocoma, Plohophorus?, Tetrastylomys, and Zygolestes). 3) Both the Andalhuala Formation and Huayquerian localities in Buenos Aires and La Pampa provinces: Achlisictis, Macroeuphractus, Doedicurinae (Eleutherocercus), Kiyutherium, Paleocavia, Promacrauchenia?, Carnivora (Cyonasua), and Achlysictis. 4) The type Chasicoan: Tetrastylus, Potamarchus, Carlesia, Diaphoromys, Gyriabrus, Lagostomopsis, Cardiomys, Parodymis?, Cardyatherium, Chasicotatus, Proeuphractus, Kraglievichia, Octomylodontinae (Octomylodon), Protomegalonyx, Brachytherium, Toxodontherium (in Chiquimil), Dinotoxodon, Protypotherium, and Cullinia? Consequently, the «Conglomerado osífero» shares 18 (20?) first generic occurrences with Huayquerian localities and 16 (19?) with Chasicoan localities (figure in parenthesis: certain records plus doubtful records).

11. The «Conglomerado osífero» also shares with the type Chasicoan several taxa that are unknown in other levels (Tables 1-3): Parodimys (Vivero Member), Octomylodon, Protomegalonyx, Protypotherium (genus that is known from the Santacrucian) and Cullinia? However, Protomegalonyx, Octomylodon and Protypotherium correspond certainly or probab ly to different species (Scillato Yané, 1977a,b; MB, personal observation), Parodimys is based on one tooth and the identification of Cullinia in the «Conglomerado osífero» is uncertain (Vucetich and Bond, personal observations).

12. The «Conglomerado osífero» shares with the Andalhuala Formation and the Pampean Huayquerian localities several taxa that are unknown from older levels: Parahoplophorus, Pyramiodontherium, Sphenotherus, Protabrocoma, Tetrastylomys and Kiyutherium. Besides, the «Conglomerado osífero» shares with the Andalhuala Formation or the Pampean Huayquerian localities several species that are unknown from older levels: Xotodon foricurvatus, Promacrauchenia antiqua, and Cyonasua argentina?

13. We regard here the first records shared with the Chasicoan as lineages that originated during this time and perdurated in younger times. Quite the contrary, the numerous first records shared with Huayquerian localities establish a minimum age for the «Conglomerado osífero» (which is here considered older than the type Montehermosan with which shares two taxa; see above). We find particularly significant the first record in South America of the family of Holarctic origin Procyonidae, which is perhaps represented by the same species both in Catamarca and Entre Ríos (Cyonasua argentina; Marshall and Patterson, 1981). Cyonasua is the first immigrant from North America of the major biogeographic late Cenozoic event named "Great American Biotic Interchange." This event deeply transformed the South American mammal fauna: presently about 50% of species is Holarctic in origin. Besides, some other taxa of higher than genus level appear for the first time in the Huayquerian and the "Conglomerado osífero:" Myocastoridae, Abrocomidae, Neuryurini, Doedicurinae.

14. Consequently, the significative secondary mixture of Pansantacrucian, Araucanian and Panpampean taxa (see Reig, 1957; Pascual and Odreman Rivas, 1971; Marshall et al., 1983) present in the «Conglomerado osífero» is not sustained. We regard that the «Conglomerado osífero» (and the fauna enclosed) does not represent a long lapse. With the present evidence, the «Conglomerado osífero» appears to be Huayquerian in age.

15. The base of Huayquerian is located at about 9 Ma (Flynn and Swisher, 1995). According to Flynn and Swisher (1995), the available radioisotoic dates and location of the boundary within the early part of Chron C3Ar, and using chron terminology and the time scale of Cande and Kent (1995) and Berggren et al. (1997), the best estimate for the Huayquerian/ Montehermosan boundary is about 6.8 Ma, and certainly older than 6.5 Ma. Actually, this estimate is not for the boundary but to the youngest Huayquerian beds known. Beds overlying the Andalhuala Formation possibly are Chapadmalalan in age (see Cione and Tonni, 1996).

Flynn and Swisher (1995) indicate that the Huayquerian to Montehermosan interval is relatively well sampled paleomagnetically in Bolivia and northwestern Argentina. However, the «Montehermosan» sections might be Chapadmalalan in age (Cione and Tonni, 1996).

16. The Huayquerian is so correlated with the Tortonian of the Geologic Time Scale (11.2 to 7.1 Ma; Gradstein and Ogg, 1996).

17. The «Conglomerado osífero» does not share Proeuphractus and Vetelia with the Chasicoan.

These taxa occur in the Huayquerian beds at the Chasicó area that were considered as an early Huayquerian (Macrochorobates scalabrinii Biozone; Tonni et al., 1998). However, it is too premature to atribute a younger age than Macrochorobates scalabrinii Biozone to the «Conglomerado osífero.»

18. The presence of Cyonasua permits to correlate approximately the «Conglomerado osífero» and the Andalhuala Formation with those North American beds of Hemphillian age where the first South American immigrants occur for the first time (Marshall, 1985 but see Pascual et al., 1965 for a different view).

Correlation with the «Puelchan»

The «Formación» Puelche (or informally the «Puelchan») occurs deep in the subsoil of the Pampean region. The «Puelchan» is today based on thick, water-saturated, fluvial sands (and only known by drilling; Sala and Auge, 1970; Pascual and Odreman Rivas, 1971). The «Puelchan» also overlies the marine Paraná Formation (Middle Miocene-earliest Late Miocene, Cione, 1988).

Santa Cruz (1972) formally designated this unit as the Puelche Formation. This name is not acceptable for it is not geographic; it refers to an Indian tribe from Patagonia. However, it is worthy of formal recognition (following North American Comission on Stratigraphic Nomenclature, 1983, p. 851) for its uniqueness and economic importance. All the fossils that are known from this unit have been obtained from drilling operations by means of suction pumps, without any kind of stratigraphic control (see synthesis of Rusconi, 1948, 1949, and also see Castellanos, 1936). In the same unit, marine vertebrates typical of the marine Paraná Formation and the «Conglomerado osífero» occur: Carcharias acutissima, Isurus hastalis, Carcharhinus spp., Myliobatoidei and Sciaenidae (Rusconi, 1948; personal observation ALC) along with terrestrial vertebrates (toxodontid and rodents; see Rusconi, 1948, 1949; Cione and Tonni, 1995; Bond, 1999; Bond et al., 1995; Bond and López, 1998). However, these remains formed the basis for speculating that the mammals comprised an ancient pampean fauna that could well be «Ensenadense basal» (Pascual et al., 1965) or older, but always pampean (Simpson, 1940). This is despite the fact that «mammal remains from the Puelche are, in most cases, fragmentary and their determination is according to Pascual et al. (1965, p. 180), more doubtful than believed by Rusconi» (Marshall et al., 1984, p. 24). Pascual et al. (1965) established that the fauna had a post-Chapadmalalan aspect and included Ensenadan taxa. Despite the lack of stratigraphic control, Pascual et al. (1965), Reig (1981), and Marshall et al. (1984; and all other workers) included the mammals from the «Puelchense» in the «Uquian» faunal list, and even correlated the «Puelchense» with the lower part of «Uquian Land-mammal age" (cf. Kraglievich, 1952; Reig, 1981).

We consider that the presence of the abundant Miocene vertebrates and the stratigraphic relationships confirm the correlation of at least the base of the Puelchan beds with the Ituzaingó Formation. We identify no Marplatan (the age post-Chapadmalalan and pre-Ensenadan that replaces the "Uquian age;" see Cione and Tonni, 1995) from the Puelchan beds.

Biogeography

Marine vertebrates

Genera of marine fishes in the Paraná Formation are those known from the warmer part of the Argentinian Biogeographic Province (sensu López, 1964; see Cione, 1978, 1988). The fauna is integrated by inhabitants of the shelf, probably inner shelf. No typical oceanic taxon was found yet.

Remarkable is the presence of heterodontid sharks, which presently do not inhabit the Atlantic Ocean. Other sharks such as pristiophorids were detected in late Oligocene-Middle Miocene beds in Patagonia. Heterodontus and pristiophorid species were almost worldwide in the Tertiary (Cappetta, 1987; Cione, 1988; Cione and Expósito, 1980). Heterodontus species live in the Pacific today (Compagno, 1984), whereas pristiophorids do not inhabit modern South American Atlantic and Pacific coasts (Compagno, 1984). Presently, only a small population of the endemic species Pristiophorus schroederi occurs in the (northwestern) Atlantic (Springer and Bullis, 1960). Both groups greatly reduced their distribution after the Miocene. The finding of Pristiophorus in the Puerta del Diablo Formation of Patagonia and Heterodontus in the Paraná Formation constitute the last records of these genera in the South Atlantic and in the Atlantic, respectively. Both represent an example of extirpation in a particular area and persistence in other (Cione and Azpelicueta, in preparation).

The cetaceans Pontoporiidae were also common in the northern South Pacific (north of Chile and south of Perú, Cozzuol, 1996), in the North Pacific (Barnes, 1985) and North Atlantic.

The presence of pontoporiids in the Paraná Formation suggest a biogeographical connection with those regions, in a time in which the Central American seaway was still open.

Dioplotherium, apparently present in those deposits, was also found in northern Brazil (Pirabas Formation, de Toledo and Domning, 1991) and in the North Atlantic and Pacific (Domning, 1989). Balaenopteirds were proposed to be originated in the tropical Atlantic not before than late Middle Miocene, but they appeared worldwide in the record by the Late Miocene, as is the case of Paraná Formation.

If the Monachus affitinities of Poperiptychus argentinus are confirmed, this group is also known to have a tropical distribution.

Consequently, aquatic mammals indicates stronger connections South-North than with others localites of the southern Hemisphere.

Aquatic continental vertebrates

The Neotropical Region is divided into two phenetic subunits according to recent fish distribution (Ringuelet, 1975; Arratia et al., 1983): the Brazilian and Austral subregions.The Austral Subregion includes Patagonia, Cuyo, and southern-central Chile (Ringuelet, 1975; Arratia et al., 1983; Arratia, 1997). The northern boundary of the Austral subregion is defined in Argentina by the San Juan-Desaguadero-Curacó-Colorado drainages. The Brazilian Subregion occupies the rest of South America and Central America. The Brazilian Subregion is the richest area in fish diversity and the Austral Subregion is one of the less diverse areas in the world (less than 25 species; Ringuelet, 1975; Almirón et al., 1997; Arratia, 1997; Casciotta et al., 1999). The Brazilian diversity dramatically diminishes south of the Río de la Plata today.

Miocene freshwater fishes from the Paraná area are tipically brazilic and no austral taxon was detected.

Fishes, crocodiles, cetacean, and sirenids from the "Conglomerado osífero" are related to those of the late Miocene Laventan beds (Langston, 1965; Langston and Gasparini, 1997; Cione, Lundberg and Machado Allison, en preparation), the Late Miocene beds of the Peru and Brazilian Acre (Boquentin et al., 1989; Rancy et al., 1989; Bocquentin and Souza Filho, 1990; Frailey, 1986; Gasparini, 1996) and the late Miocene–Lower Pliocene beds of Urumaco, Venezuela (Buffetaut, 1982; Gasparini, 1996). La Venta, Acre and Paraná sharethe tetropods Caiman, Mourasuchus and Gryposuchus. Acre and Paraná also share the tetropods Ischyrorhynchus, Saurocetes and Ribodon

Presently, the Paraná-Uruguay-Plata basin is practically isolated from the Amazonian basin.

The presence of similar freshwater aquatic vertebrates with Miocene beds from Colombia (present Magdalena basin), Venezuela and the Brazilian Amazonia seems to indicate hydrographic relationships that does not exist today. The occurrence of iniid cetaceans, trichechid sirenians and a very high diversity of crocodiles also is suggestive of warmer climate than present.

Terrestrial vertebrates

Terrestrial vertebrates show a very high diversity both taxic and in inferred habits. The heterogeneous landscape, controlled by one or several rivers favoring the development of varied vegetation in a reduced area and the presence of neighbouring open areas could explain that diversity.

Temperatures and humidity were higher in the whole central and northwestern Argentina area what is clearly evidenced by the fauna and flora found from the "Araucanense," the Huayquerian beds of the Pampean and Mesopotamic areas. However, among the terrestrial vertebrates, xenarthran and notoungulate taxa indicate that the Mesopotamic area was already a biogeographic area different to that of the Pampean and northwestern Argentina (Scillato Yané, 1975b), more closely related to Uruguay and the Brazilian Acre areas (see below) at least since the Late Miocene. Consequently, the Guayano-Brazilic dominion, as it is known today, it was probably beginning to develope. However, rodents, xenarthrans, ungulates, marsupials and carnivores showed also affinities with Catamarcan localities. The typical Central or Subandean Dominion of the Andean-Patagonian Subregion (Ringuelet, 1961; Figure 9) was not yet beginning to differenciate.

The absence of some taxa which are recorded in coeval sediments of relatively nearby regions (Glyptodontinae glyptodonts, and Myrmecophagidae and Cyclopidae vermilinguans) is noteworthy. Notoungulates and caviomorphs showed also high endemism. During the Miocene the zoogeographic and environmental characteristics of this part of the Mesopotamia must have been quite peculiar. This hypothesis is not hindered by the analysis of the rest of the biota and the geological information. With the available evidence, the closest affinities of the «Mesopotamian» xenarthrans may be found within those of the Miocene-Pliocene of Uruguay.

The "Conglomerado osífero" fauna is also important for studying the evolution of birds in relation to the "Great American Biotic Interchange" because it corresponds to a older moment than the establishment of a definitive connection between South and North America. The fossil record shows that flightless birds (and those with reduced capacity of flight) such as Rheiformes, Tinamiformes, "phororacoids," and Opisthocomidae evolved in complete isolation during most of the Tertiary (Tambussi and Noriega, 1996). Besides this, some flying birds such as Teratornithidae and the "suboscines" passeriforms did not cross the Panama gap until the isthmus was established (Tambussi and Noriega, 1996; Noriega, 1998). Other birds (eg dendrochenin anatids and palelodin flamingos) were not biogeographically isolated. This late evidence confirms the hypothesis favoring a significative biogeographic conexion of South American bird faunas with those of North America and Europe (Martin, 1983; Rasmussen and Kay, 1992).

Environment

Marine

The high marine level of the middle Miocene sea permitted the ingression of marine waters in the Chacopampean plains at least to Paraguay and Bolivia (Uliana and Biddle, 1988; Marshall et al., 1993; Cione and Cozzuol, in preparation). In the south, the marine influence was restricted to northeastern Patagonia. A warm temperate Miocene ichthyofauna occurs in the top of theParaná Formation. The assemblage from Paraná is different from the Patagonian ichthyofauna but it is similar to that present at the same latitude in the Atlantic coast of southern Brazil (Cione, 1978). Whereas at Paraná carcharhinids, hemigaleids, and odontaspidids dominate, Patagonian ichthyofaunas are ruled by lamnids. Cetacean from the Paraná Formation also do not indicate temperatures very different to that present in the same latitude. However, the sirenian, the pinniped and the invertebrates suggest warmer waters for Paraná, which can be extended to northern Patagonia on the basis of invertebrates (Del Río, 1988).

Remarkably, contrasting with the late Oligocene-early Miocene ichthyofaunas, Middle Miocene shark assemblages appears to have been poorly diversified in Patagonia (Cione, 1978, 1988; Cione and Tonni, 1981; Perea et al., 1985; Perea and Ubilla, 1989, 1990).

The elasmobranch association present in the Paraná Formation suggest normal marine salinity.

Continental

Neither dipnoan nor anuran were recorded in the area. Taking into consideration the relatively good preservation of dipnoan teeth, lack of these fishes could be related to the absence of appropriate lenthic environments (but see below evidence from birds). The absence of anuran could be due to a defect of preservation and collection.

The paleogeographic location of Paraná, in the subtropical to temperate belt is also confirmed by the absence of crocodilids, podocnemidids, and primates. Today, South American crocodylids inhabit strictly tropical regions. However, the lack of primates would be due to insuficient preservation.

The taxonomic reptile diversity, especially crocodiles from the «Conglomerado osífero» suggest varied paleoenvironments. The predominance of aquatic birds in the «Conglomerado osífero» support the presence of woody lowlands and swamps along the river banks. This type of environments is also a requisite for the trichechids and iniids, which need lakes associated to the main river to live, feed and reproduce. Besides, rheas and fororhacs suggest a savanna-like environments near the riversides (Noriega, 1994, 1995).

Glyptodontids are very diversified in the "Conglomerado osífero." The glyptodontid diversity from the "Araucanian" of Catamarca and Tucumán is smaller. However, the main difference between both faunas lies in the very scarce glyptodontid frequency in Entre Ríos in comparison with their extraordinary abundance in the Northwest of Argentina. As middle to large sized mammals, all these glyptodonts must have preferred more open environments (savannas, grasslands, and herbaceous steppes). These conditions were probably common in the northwest but not in the Paraná area. Here, glyptodonts are represented mainly by isolated scutes, small fragments of carapace or skeleton, with clear evidence of post-mortem transportation. This suggests that they lived near the gallery forests of the «pre-Paraná», but not into them.

The tardigrade diversity must have been related to a heterogeneous landscape, surely controlled by a river (or several rivers), favoring the development of a varied vegetation cover in reduced areas.

Comparing with other faunas from the Late Miocene and Pliocene of South America, proterotheriids are extremely abundant in the "Conglomerado osífero," confirming the relation of these mammals to woody and wet environments. Interatheriidae Interatheriinae notoungulates also seem to have been related to woody and wet environments while Hegetotheriidae, especially the "rodentiform" Pachyrukhinae would have inhabited more open and dry environments. An analogous situation was discovered in the Colloncuran faunas of Argentina and Laventan faunas of Colombia where Pachyrukhinae were very abundant in Patagonia, although Interatheriinae were also present. On the contrary, in Colombia, where the environment seem to have been more tropical, woody and wet, Pachyrukhinae are absent (Cerdeño and Bond, 1998) and only an endemic and large taxon of Interatheriinae, though smaller than Munizia occur.

The occurrence of a porcupine rodent support the presence of forested environments, as well as the biogeographic conexion with northern South America. The absence of octodontid rodents suggest the possible absence of arid environments. Octodontids are common in western and central Argentina (Central or Subandean Dominion).

Procyonids are medium-sized, good swimmers omnivores that mainly inhabit forested environments (Bond, 1986).

Among the terrestrial vertebrates, no primate was recorded. The lack of monkeys would be due to a defect of preservation because global temperatures were higher than present, primates had been recorded until Colloncuran times in Patagonia, forested areas certainly occurred in the area of Paraná (evidenced by the abundant wood present in the sediments and the association of terrestrial vertebrates) and other arboral mammals such as porcupines are now known in the "Conglomerado osífero."

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following institutions and people: Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas, Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica, Comisión de Investigaciones Científicas de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo for permanent finantial support.

Centro de Investigaciones Científicas y Transferencia de Diamante, for assistance in the area.

F. Aceñolaza and R. Herbst, for the invitation to participate in the present volume. C. Ceruti, for assistance in Paraná. José Laza, for preparation of materials. Cecilia Deschamps for assistant to some of the authors.

Carlos Tremouilles, for drawings. Carlos Steger, for loaning valuable materials.

Bibliography

Aceñolaza, F.G. 1976. Consideraciones bioestratigráficas sobre el Terciario marino de Paraná y alrededores. Acta Geológica Lilloana 13: 91-107.

Aceñolaza, P.G. and Aceñolaza, F.G. 1996. Improntas foliares de una Lauraceae en la Formación Paraná (Mioceno superior), en la Villa Urquiza, Entre Ríos. Ameghiniana 33: 155-159.

Aceñolaza, F.G. and Aceñolaza, G. 1999. Trazas fósiles del Terciario marino de Entre Ríos (Formación Paraná, Mioceno medio), República Argentina. Boletín de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias, Córdoba 64: 209-233.

Aceñolaza, F.G. and Sayago, J.M.. 1980. Análisis preliminar sobre la estratigrafía, morfodinámica y morfogénesis de la región de Villa Urquiza, provincia de Entre Ríos. Acta Geológica Lilloana 15: 139-154.

Albino, A. 1996. The South American fossil Squamata (Reptilia: Lepidosauria). In: G. Arratia (ed.), Contributions of Southern South America to Vertebrate Paleontology, München Geowissenschaft Abhandlungen 30, pp. 185-202.

Alessandri, G. 1896. Ricerche sui pesci fossili de Paraná. Atti della Reale Academia di Scienze di Torino 31: 1-17.

Almirón, A., Azpelicueta, M.M., Casciotta, J. and López Cazorla, A. 1997. Ichthyogeographic boundary between the Brazilian and Austral subregions in South America, Argentina. Biogeographica 73: 23-30.

Ambrosetti, J. 1890. Observaciones sobre los reptiles fósiles oligocenos de los terrenos terciarios antiguos del Paraná. Boletin Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Córdoba 10: 409-426.

Ambrosetti, J. 1893. Contribución al estudio de las tortugas oligocenas de los terrenos terciarios antiguos del Paraná. Boletín Instituto Geográfico Argentino 14: 489-499.

Ameghino, F. 1883a. Sobre una colección de mamíferos fósiles del Piso Mesopotámico de la Formación Patagónica recogidos en las barrancas del Paraná por el Profesor Pedro Scalabrini. Boletín de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Córdoba (República Argentina) 5 (entrega 1a): 101-116.

Ameghino, F. 1883b. Sobre una nueva colección de mamíferos fósiles recogidos por el Profesor Scalabrini en las barrancas del Paraná. Boletín de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Córdoba 5: 112-113.

Ameghino, F. 1885. Nuevos restos de mamíferos fósiles oligocenos recogidos por el profesor Pedro Scalabrini y pertenecientes al Museo Provincial de la ciudad de Paraná. Boletín de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Córdoba 8: 3-207.

Ameghino, F. 1886. Contribución al conocimiento de los mamíferos fósiles de los terrenos Terciarios antiguos del Paraná. Boletín de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Córdoba (República Argentina) 9: 3-226.

Ameghino, F. 1887. Observaciones generales sobre el orden de los mamíferos extinguidos llamados toxodontes (Toxodontia) y sinopsis de los géneros y especies hasta ahora conocidos. Anales del Museo de La Plata, 1 (entrega 1): 1-66.

Ameghino, F. 1889. Contribución al conocimiento de los mamíferos fósiles de la República Argentina. Actas de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Córdoba. 6: XXXII + 1028, Atlas: 98 láms.

Ameghino, F. 1891. Caracteres diagnósticos de cincuenta especies nuevas de mamíferos fósiles argentinos. Revista Argentina de Historia Natural 1: 129-167.

Ameghino, F. 1892. Répliques aux critiques du Dr. Burmeister sur quelques genres de mammiféres fossiles de la République Argentine. Boletín de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Córdoba (República Argentina), 12 (Entrega 4a): 437-469.

Ameghino, F. 1898. Sinopsis geológico-paleontológica. En: 2do Censo de la República Argentina. I. Territorio, Buenos Aires: 1- 500.

Ameghino, F. 1904a. Recherches de morphologie phylogénétique sur les molaires supérieures des ongulés. Anales del Museo Nacional de Buenos Aires 9 (ser. 3a, 3): 1-541.

Ameghino, F. 1904b. Nuevas especies de mamíferos, cretáceos y terciarios de la República Argentina. Anales de la Sociedad Científica Argentina 20: 56-58.

Ameghino, F. 1906. Les Formations Sedimentaires du Crétacé Supérieur et du Tertiaire de Patagonie avec un paralléle entre leurs faunes mammalogiques et celles de l’ancien continent. Anales del Museo Nacional de Buenos Aires 15 (ser. 3a, 8): 1-568.

Arratia, G., Peñafort, B. and Menu-Marque, S, 1983. Peces de la Región Sureste de los Andes y sus probables relaciones biogeográficas actuales. Deserta 7: 48-107.

Arratia, G. and Cione, A.L. 1996. The fossil fish record of Southern South America. In: G. Arratia (ed.). Contributions of Southern South America to Vertebrate Paleontology, München Geowissenschaft Abhandlungen 30, pp. 9-72.

Arratia, G. 1997. Brazilian and Austral freshwater fish faunas of South America. A contrast. In: Tropical biodiversity and systematics. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Biodiversity and Systematics in Tropical Ecosystems, Bonn, 1994: 179-186.

Báez, A.M. and Gasparini, Z. 1977. Orígenes y evolución de los anfibios y reptiles del Cenozoico de América del Sur. Acta Geológica Lilloana 14: 149-232.